Even if you’ve never read the sci-fi best-seller Ender’s Game, in which a child is trained to become a military commander in order to thwart an alien invasion, you may have heard something about the hateful and extremist politics of its author, Orson Scott Card. Card has repeatedly condemned homosexuality in no uncertain terms and has compared Obama and his supposed “urban gangs” to Hitler and the Nazis. These views have posed problems for the film adaptation, which opened last night and is being boycotted by some supporters of equal rights for all. Those behind the movie have understandably defended the book by saying that it preaches tolerance and really has nothing to do with Card’s ugly political views.

That’s true—up to a point. But Card, and his politics, can’t be separated from his book entirely. And the movie leaves out much of what might remind people that the man who envisioned this universe is politically paranoid and emphatically anti-gay. Some cuts may have been made simply to keep the movie under 2 hours. But other changes have nothing to do with running time.

Consider the book’s aliens. Throughout the book, they’re called “buggers,” a nickname that derives from their insectoid quality. But the word bugger is principally a derogatory slang term for gay men and gay sex, meaning “to sodomize” as a verb and one who engages in “sodomy” as a noun. Granted, the slang is chiefly British, and it’s possible that the American Card either wasn’t aware of it or didn’t expect his readers to be. But it makes for awkward reading today. (At one point a character insults his rivals by calling them “bugger-lovers.”) In the movie, the buggers are referred to throughout by another name also used by Card in the Ender series, but not in the first book: “the Formics” (formic means “of or relating to ants”). This is the term the movie uses even when Ender and his older brother play “Formics and Astronauts” (called “Buggers and Astronauts” in the book, it appears to be a sci-fi version of “Cowboys and Indians”).

Then there’s the homophobic bullying Ender both experiences and dishes out. One character is mocked for being a “butt-wiggler.” And after Ender gets bullied by a kid named Bernard, he hacks into the school’s texting system and sends everyone a message that appears to come from God: “Cover your butt. Bernard is watching,” it reads. Later, he sends one that appears to come from Bernard: “I love your butt. Let me kiss it,” the message says. Card is not necessarily endorsing such taunting—one fan has argued that Ender is in fact more queer than readers realize—but Ender is the hero and readers are probably tempted to cheer on his revenge.

None of this is in the movie, though. Also omitted: the book’s many references to politics back on Earth. In the book, Ender’s parents must be secretive about their religious views—his father is Catholic and his mother, like Card, is Mormon—because the free practice of religion is no longer allowed. Card himself believes that religion is under fire in the present-day United States.

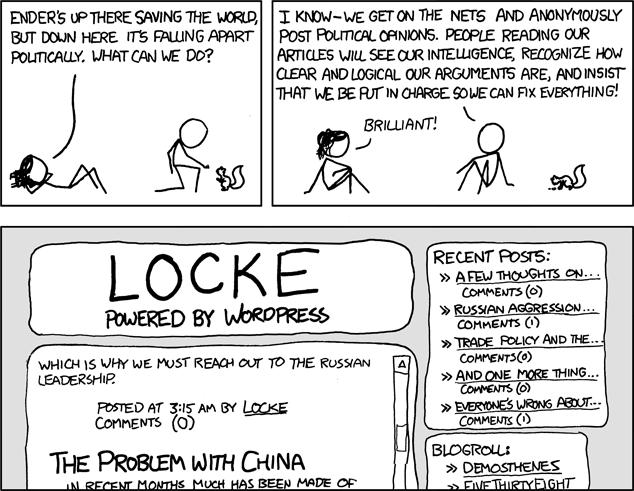

Much is made in the book of the uneasy, Cold War-like détente that the threat of alien invasion has created. There’s a major storyline about the efforts of Ender’s sadistic brother, Peter, to capitalize on those political tensions and take over the world. He is explicitly compared to Hitler, and bears a passing resemblance to Card’s later visions of Barack Obama; the scenario in general evokes Card’s longstanding fears of a “new world order.”

Ultimately, it’s more complicated than that: While Peter succeeds, he also matures, and does not become the vicious dictator he seems destined to become. And it’s quite possible the filmmakers omitted all this out of concern for the movie’s running time. Still, its absence is conspicuous. And while I think the absence of Peter’s storyline makes the movie less interesting than the book, it, like these other cuts, also makes it easier for the filmmakers to say that their movie has nothing do with the unfortunate politics of Orson Scott Card.

Even if you’ve never read the sci-fi best-seller Ender’s Game, in which a child is trained to become a military commander in order to thwart an alien invasion, you may have heard something about the hateful and extremist politics of its author, Orson Scott Card. Card has repeatedly condemned homosexuality in no uncertain terms and has compared Obama and his supposed “urban gangs” to Hitler and the Nazis. These views have posed problems for the film adaptation, which opened last night and is being boycotted by some supporters of equal rights for all. Those behind the movie have understandably defended the book by saying that it preaches tolerance and really has nothing to do with Card’s ugly political views.

That’s true—up to a point. But Card, and his politics, can’t be separated from his book entirely. And the movie leaves out much of what might remind people that the man who envisioned this universe is politically paranoid and emphatically anti-gay. Some cuts may have been made simply to keep the movie under 2 hours. But other changes have nothing to do with running time.

Consider the book’s aliens. Throughout the book, they’re called “buggers,” a nickname that derives from their insectoid quality. But the word bugger is principally a derogatory slang term for gay men and gay sex, meaning “to sodomize” as a verb and one who engages in “sodomy” as a noun. Granted, the slang is chiefly British, and it’s possible that the American Card either wasn’t aware of it or didn’t expect his readers to be. But it makes for awkward reading today. (At one point a character insults his rivals by calling them “bugger-lovers.”) In the movie, the buggers are referred to throughout by another name also used by Card in the Ender series, but not in the first book: “the Formics” (formic means “of or relating to ants”). This is the term the movie uses even when Ender and his older brother play “Formics and Astronauts” (called “Buggers and Astronauts” in the book, it appears to be a sci-fi version of “Cowboys and Indians”).

Then there’s the homophobic bullying Ender both experiences and dishes out. One character is mocked for being a “butt-wiggler.” And after Ender gets bullied by a kid named Bernard, he hacks into the school’s texting system and sends everyone a message that appears to come from God: “Cover your butt. Bernard is watching,” it reads. Later, he sends one that appears to come from Bernard: “I love your butt. Let me kiss it,” the message says. Card is not necessarily endorsing such taunting—one fan has argued that Ender is in fact more queer than readers realize—but Ender is the hero and readers are probably tempted to cheer on his revenge.

None of this is in the movie, though. Also omitted: the book’s many references to politics back on Earth. In the book, Ender’s parents must be secretive about their religious views—his father is Catholic and his mother, like Card, is Mormon—because the free practice of religion is no longer allowed. Card himself believes that religion is under fire in the present-day United States.

Much is made in the book of the uneasy, Cold War-like détente that the threat of alien invasion has created. There’s a major storyline about the efforts of Ender’s sadistic brother, Peter, to capitalize on those political tensions and take over the world. He is explicitly compared to Hitler, and bears a passing resemblance to Card’s later visions of Barack Obama; the scenario in general evokes Card’s longstanding fears of a “new world order.”

Ultimately, it’s more complicated than that: While Peter succeeds, he also matures, and does not become the vicious dictator he seems destined to become. And it’s quite possible the filmmakers omitted all this out of concern for the movie’s running time. Still, its absence is conspicuous. And while I think the absence of Peter’s storyline makes the movie less interesting than the book, it, like these other cuts, also makes it easier for the filmmakers to say that their movie has nothing do with the unfortunate politics of Orson Scott Card. — Slate.com